12 Key Points about Cycle Infrastructure Design

11th November 2020

In July this year, the Department for Transport (DfT) published LTN 1/20, also known as Cycle Infrastructure Design (CID). It is a genuinely excellent document.

CID provides guidance on how to build cycle infrastructure in England and Northern Ireland. Local authorities have their own highways guidance and standards, but CID is now the recommended basis for the cycling elements of local standards.

With the publication of CID, we have truly first-class cycle infrastructure standards; now all we need is the cycle infrastructure to match.

The document itself is 188 pages. I’ve written a (long) summary of it, as well as Key Points for North Yorkshire County Council and Key Points for Harrogate Borough Council.

Here are just 12 key points.

1) Cycling must no longer be Treated as Marginal

The Foreword to CID by the Minister with responsibility for cycling states:

Cycling must no longer be treated as marginal, or an afterthought. It must not be seen as mainly part of the leisure industry, but as a means of everyday transport. It must be placed at the heart of the transport network, with the capital spending, road space and traffic planners’ attention befitting that role.

Foreword, Cycle Infrastructure Design

In truth, cycling has been treated as marginal for years by North Yorkshire County Council (NYCC), and if the Minister’s message reaches them, the change in approach will be transformative.

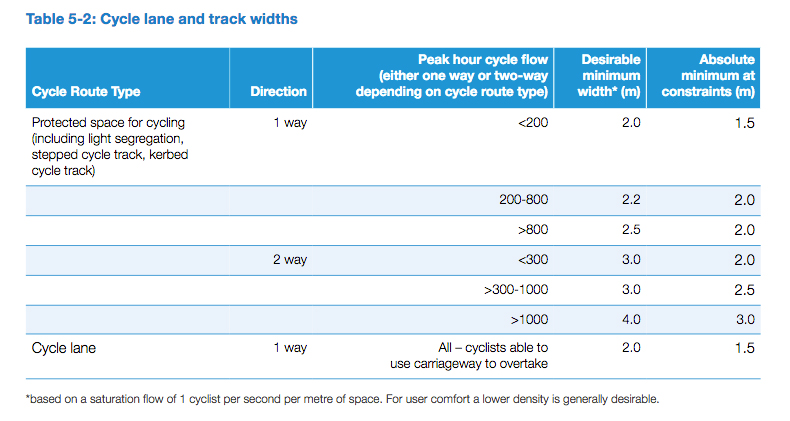

CID contains five Core Design Principles, and twenty-two Summary Principles. Summary Principle 5 tells local authorities to design for thousands of cyclists a day, and for non-standard cycles including cargo bikes. It says that cycle tracks should be 2m wide, or 3-4 m for bi-directional tracks, to allow for overtaking.

If NYCC put the Foreword and Summary Principle 5 into practice, it will mean that cycling really is at the heart of the local transport network.

One of many local examples of treating cycling as marginal, and failing to put it at the heart of the transport network, is the Dragon Road passage route over the railway. This is a main, signed cycle route where cycling is prohibited, with a CYCLISTS DISMOUNT sign.

We’re conditioned to be unsurprised by this sort of poor provision, but really a cycle route where you’re forbidden to cycle should be regarded as unacceptable.

2) There should be a Coherent Network of Routes

A cycle network should allow people to reach their day-to-day destinations along routes that connect and are of a consistent high quality. That’s according to the first of the Core Design Principles, Coherence. It shouldn’t need to be said, but it does.

Related to this are provisions of CID about signs: designers are told that CYCLISTS DISMOUNT signs are very rarely appropriate and should not normally be used on a well-designed facility; and END OF ROUTE signs should be used sparingly and only when it’s unavoidable.

In Harrogate District, designers seem to be keen as mustard to put up as many of these signs as possible. If only they put the same amount of effort into designing Coherent cycle routes, we’d be in a much better position.

One example of a failure to produce a Coherent route is Harlow Moor Road/Cornwall Road/Penny Pot Lane. There are sections of this route with shared use pavement, and sections without. What’s the point of that?

The type of infrastructure on that route is also unacceptably poor, which brings me on to the next point.

3) No Shared Use Pavements in Urban Areas

Cycles must be treated as vehicles, not as pedestrians. On urban streets, cyclists must be physically separated from pedestrians and should not share the same space with pedestrians.

Summary Principle 2, Cycle Infrastructure Design

CID explains that shared use facilities are not favoured by either pedestrians or cyclists. (It may be appropriate away from streets, in places like canal towpaths or parks).

Shared use pavements often seem to be the default in Harrogate. Even now, a new one is being built on Harlow Moor Road (the so-called ‘Miller Homes cycleway’).

Anyone who stands and watches what happens at existing shared use pavements (for example Penny Pot Lane, Harlow Moor Road, or Beckwith Head Road) will see that they are ignored by people on bikes. Because they are inconvenient, involving negotiating your way past people on foot and stopping at every side street, they won’t attract any new cyclists either.

NYCC need to stop defaulting to shared use pavements; it’s not a good enough standard.

4) Cycle Facilities must be Safe

Cycle infrastructure must be Safe, and perceived to be Safe, according to the third Core Design Principle. This point is reinforced in the Summary Principles.

Cyclists must be physically separated and protected from high volume motor traffic, both at junctions and on the stretches of road between them…On roads with high volumes of motor traffic or high speeds, cycle routes indicated only with road markings or cycle symbols should not be used as people will perceive them to be unacceptable for safe cycling.

Summary Principle 3, Cycle Infrastructure Design

A further passage about fear of motor vehicles is worth highlighting.

Motor traffic is the main deterrent to cycling for many people with 62% of UK adults feeling that the roads are too unsafe for them to cycle on…The need to provide protected space for cycling on highways generally depends on the speed and volume of motor traffic. For example, in quiet residential streets, most people will be comfortable cycling on the carriageway even though they will be passed by the occasional car moving at low speeds. On busier and faster highways, most people will not be prepared to cycle at all, or some may unlawfully use the footway.

Para 4.4.1, Cycle Infrastructure Design

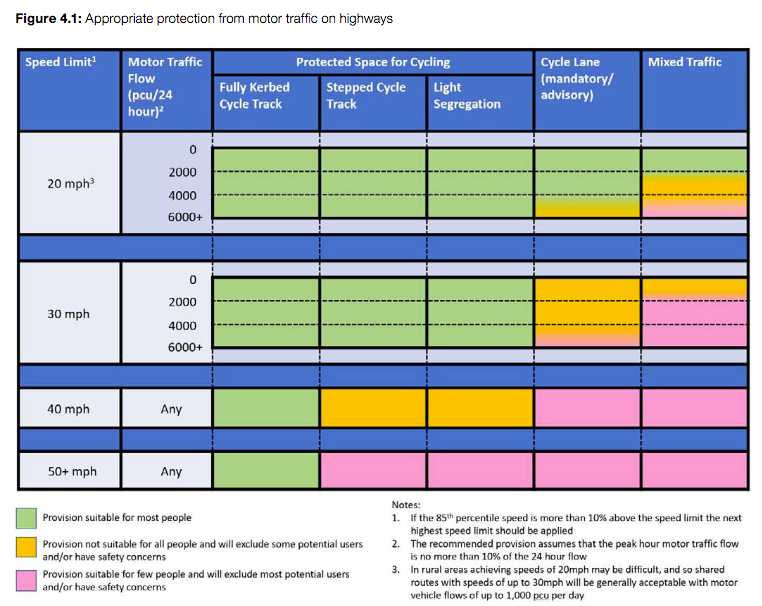

Helpfully, CID tells councils exactly when to provide protection from motor vehicles, and what sort of protection is appropriate in different situations.

5) When Infrastructure isn’t Needed

Equally, CID tells designers when cycle infrastructure isn’t needed. Most people are happy to cycle on the carriageway where speeds are low and traffic flows are light. The upper limits for inclusive cycling (para 7.1.1) are:

- 20mph and

- 2,500 vehicles a day

Traffic calming, crossings, junction treatments, and reducing use by motor traffic with modal filters or contraflow cycling on one way streets, all help to make streets more suitable for cycling in mixed traffic.

Summary Principle 17 says that bollards to prevent through traffic are a quick, cheap and effective way of making streets less hostile for cycling.

6) Cycle Routes must be Direct

Another Core Design Principle is that cycle routes should be at least as Direct as those for motor vehicles, and routes involving lots of stopping and starting are likely to be ignored.

One example of a junction that provides a good Direct route across it by bike is the crossing of West Park from Beech Grove to Victoria Avenue. The fact that drivers are not allowed to make the same movement across that junction makes it feel much safer.

Part of the Direct principle is that routes should not involve lots of unnecessary stopping and starting, and there are plenty of local examples of routes that breach this principle including Jennyfield Drive, Harlow Moor Road, and Beckwith Head Road.

Related to the Direct principle, CID says that in urban areas there shouldn’t be more than 250-400m between routes; then wherever you want to go, you can go by bike.

7) There should be a Cycling & Walking Plan

Summary Principle 8 says that cycle infrastructure must be planned as a holistic network; isolated stretches of provision are of little value.

The network of routes needs to be planned, via a Local Cycling & Walking Infrastructure Plan (LCWIP).

Harrogate District has had a number of cycling plans over the years (see Framework on the Harrogate District Cycle Action website), and the latest is a Phase 1 Harrogate Cycle Infrastructure Plan adopted by NYCC last summer. The trouble is, it’s too general.

We need specific routes and schemes. They are supposed to be in a Phase 2 report, which would be the LCWIP. It’s unclear when this is likely to be written and published.

An LCWIP is important in many ways, including for housing development – my next point.

8) Highway Schemes and Developments must include Cycling and Walking

Summary Principle 6 says there will be a presumption that future highway schemes will include provision for cycling and walking in to the standards in CID.

This applies to new developments: there should be new cycle routes connecting to and through developments and enhancing the provision for cycling when making alterations to links and junctions on existing highways.

It will not usually be acceptable to to maintain an existing poor level of service when undertaking highway improvement schemes.

Para 14.1.4, Cycle Infrastructure Design

The comments in CID about developments are not new. According to the National Planning Policy Framework, applications for development should ‘give first priority to pedestrian and cycle movements, both within the scheme and neighbouring areas.’

In Harrogate, that isn’t happening. At Persimmon’s King Edwin Park development near the Jubilee roundabout, the main route to work, schools and shopping will be Penny Pot Lane, and as there’s no Coherent cycle infrastructure, most of those journeys will be by car. There is a mud and gravel path across Killinghall Moor, but that’s likely to be an occasional leisure route.

At the big development on the A59 Skipton Road, opposite Jennyfield, there’s a shared use path along the front of the development, but it doesn’t go anywhere. People won’t be able to cycle to Aldi at Oak Beck Park unless they brave the A59 – and most people won’t do that, so they’ll probably drive.

Even where there are plans for cycle routes, they are not built promptly. Houses go up, and roads for motor vehicles appear, but cycle paths come years later, if at all. There are plans for a cycle route from the Dunlopillo site in Pannal to Harrogate, but it’s unclear exacty what will be built and when.

Without an LCWIP, it’s harder to get contributions from developers towards a Coherent plan.

Where local authorities have developed a future cycling network through an LCWIP it will enable them to seek meaningful and worthwhile contributions from new developments rather than ad-hoc and isolated measures which do not enable active travel journeys beyond the site. Para 14.2.7, Cycle Infrastructure Design

9) Cycle Lanes should be 2m Wide

One of the Core Design Principles states that cycle routes should be Comfortable. As well as good quality surfaces, this means adequate width – as mentioned above, 2m, or 3-4m for bi-directional tracks.

Adequate width is important for comfort. Cycling is a sociable activity and many people will want to cycle side by side, and to overtake another cyclist safely. It is important that cyclists can choose their own speed so that they can make comfortable progress commensurate with the amount of effort they wish to put in.

Para 4.2.15, Cycle Infrastructure Design

If a designer is wondering how wide a cycle track should be, CID has the answers.

Where a cycle track runs by a kerb an extra 20cm is needed, and where it runs by a wall, the designer should add 50cm – because in these situations, the edge of the cycle track next to the kerb or wall is not usable. There should also be buffer strips to protect cyclists from air turbulence from passing traffic and debris from the carriageway (6.2.11).

Wherever possible, space should be taken from the carriageway, not by reducing the level of service for pedestrians (para 6.1.9).

10) It’s Vital to Make Good Provision at Junctions

According to Summary Principle 21, schemes must be consistent. Abrupt reductions in the quality of provision – such as a busy high-speed roundabout – mean that an otherwise serviceable route becomes unusable by most potential users (para 4.2.4).

Safety is vital, but junctions and crossings should also enable cyclists to negotiate them in comfort without undue delay or deviation…

Preamble to Chapter 10, Cycle Infrastructure Design

An example of a very busy junction in Harrogate that fails to make provision for cycling is the Sainsbury’s junction on Wetherby Road. The Yorkshire Showground cycle route is quite good, and it continues the other side of Wetherby Road through Stonefall Park, but the crossing of Wetherby Road is difficult and dangerous, and NYCC has made no attempt to make proper provision for cycling.

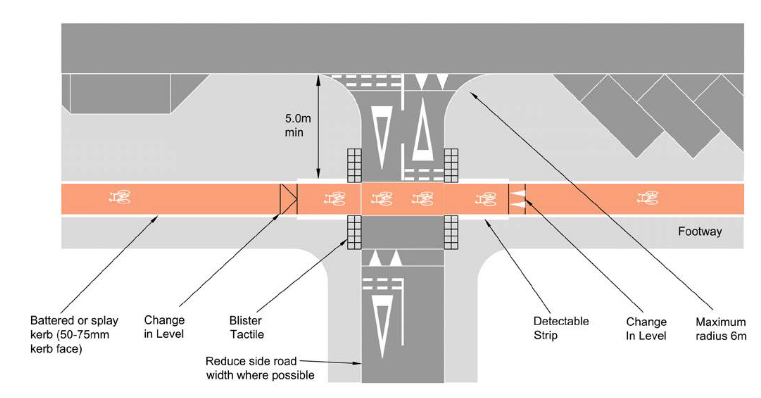

Another type of junction is where a cycle track on a main road passes minor side roads. As usual, CID provides councils with the designs they need. This one is suitable for a cycle track that’s set back from the main road (e.g. Jennyfield Drive).

11) Designers should Get on their Bikes

Designers of cycle schemes should have training, for example the Highway Engineers' Professional Certificate & Diploma in Active Travel.

They should also experience the road as a cyclist.

Ideally, all schemes would be designed by people who cycle regularly. But in every case, those who design schemes should travel through the area on a cycle to understand how this feels - and experience some of the failings...The most effective way to gain this understanding is to get out and cycle the route and observe users' behaviour.

Summary Principle 20, Cycle Infrastructure Design

12) Construction and Maintenance

Smooth, sealed solid surfaces offer the best conditions for everyday cycling (para 15.2.1). They should normally be provided in towns, cities and villages, and on commuter routes between villages. Unbound surfaces are unsuitable for utility cycling, require more maintenance, and are easily damaged by horses (15.2.8).

There is no natural sweeping effect from cyclists, so routine maintenance should include regular sweeping. Table 15-1 contains a maintenance programme for off-road routes.